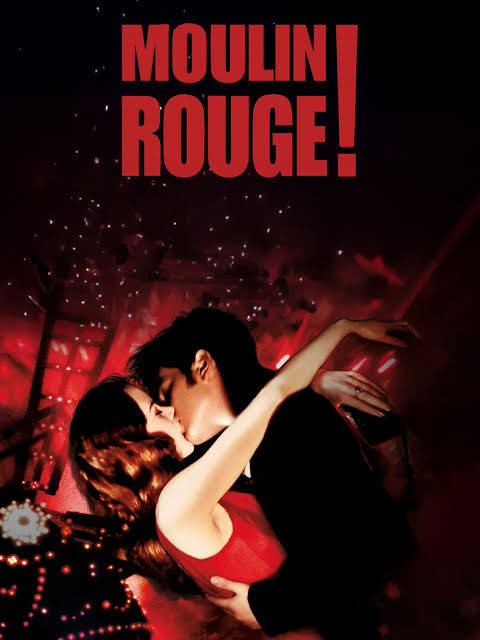

Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge! (2001) completes his vibrant Red Curtain Trilogy, following Strictly Ballroom (1992) and Romeo + Juliet (1996). Where Strictly Ballroom embraced dance as its theatrical motif and Romeo + Juliet used heightened Shakespearean language, Moulin Rouge! explodes with music—specifically, the jukebox musical. A pastiche of glamor, melodrama, and spectacle, Moulin Rouge! leans heavily into camp and theatrical excess to tell a tragic love story drenched in queerness, gender performance, and emotional abandon.

Set in 19th-century Montmartre, Moulin Rouge! follows Christian, a penniless Bohemian poet, who falls in love with Satine, a courtesan and star performer at the Moulin Rouge. Told from Christian’s perspective, the story opens on a grieving writer, recounting his doomed romance as Satine succumbs to consumption. The film’s core narrative is familiar: a love triangle between a woman, her patron, and her forbidden lover. But in Luhrmann’s hands, this tragedy is reimagined through the lens of theatrical spectacle, musical mashups, and an operatic emotional register that highlights deeper themes of gender, objectification, and economic dependence.

The Bird in the Gilded Cage

Satine (Nicole Kidman) is first introduced as the sparkling “Sparkling Diamond”—a woman literally suspended in midair on a swing, descending like a goddess above the adoring male gaze. This image recalls the metaphor of the “bird in the gilded cage”—a woman who appears beautiful and free but is trapped by her circumstances. The film leans into this symbolism: her costumes glitter, her lips bleed, her dreams die.

While Satine performs numbers like “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” and “Material Girl,” she is framed as a consumable fantasy. Her job is to sell desire, but her body and choices are controlled by men—primarily Harold Zidler, the club owner, and the wealthy Duke who seeks to possess her. Satine becomes a bargaining chip in a business transaction between men, echoing Simone de Beauvoir’s feminist critique: “A dowry or an inheritance still enslaves her to her family” (The Second Sex, 1949/2010, p. 440). Here, Satine is enslaved not by marriage, but by economic necessity and patriarchal power.

Even her declaration of “lady’s choice” is hollow—an illusion of agency masked by performance. She chooses Christian only because she mistakes him for the Duke. In reality, her choices are limited by Harold’s deals and the Duke’s money. As Beauvoir argues, “Most working women do not escape the traditional feminine world… neither society nor their husbands give them the help needed to become, in concrete terms, the equals of men” (p. 722). Satine’s labor as a sex worker may offer income, but it doesn’t offer independence.

Love as Ownership

Christian’s love for Satine is passionate and poetic, but not free from patriarchal impulses. While he does not treat Satine as cruelly as the Duke, his possessiveness emerges as the story unfolds. As the Argentinian character warns in “El Tango de Roxanne,” jealousy is inevitable when loving “a woman who sells herself.” The performance becomes a visual fever dream, underscoring Christian’s descent into violent jealousy, mirroring the Duke’s possessive obsession. Beauvoir’s assertion that “many men never accept this division between flesh and consciousness” (p. 728) is visible here—Christian struggles to love Satine as both a subject and an object, just as the Duke seeks to own her body outright.

The film critiques this dynamic while still participating in it. Luhrmann’s storytelling, framed through Christian’s male gaze, indulges in Satine’s objectification even as it mourns her lack of freedom. The tragedy is that Christian, though sympathetic, still longs to claim her love as his own. Neither man offers Satine a true escape.

Tragic Camp and Feminine Performance

Moulin Rouge! thrives on theatricality. It celebrates excess, exaggeration, and melodrama—hallmarks of camp. Like the rest of the Red Curtain Trilogy, this film intentionally blurs reality and performance, leaning into queer aesthetics. The bohemian crew’s chaotic musical—their attempt to stage a revolutionary show inside the Moulin Rouge—mirrors the narrative itself. Life and art become indistinguishable.

Satine’s entire identity is built on performance. She shifts between roles depending on who’s watching: seductress for the Duke, dreamer for Christian, breadwinner for Zidler. This shape-shifting aligns with Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity—Satine’s womanhood is not fixed but performed through repetition, costume, voice, and desire. Yet this performance is also a trap, one she cannot escape.

In one of the film’s most emotionally raw moments, Satine sings “Come What May”—the only original song in the film. It is not a performance for an audience, but a private declaration between lovers. Here, Satine momentarily steps out of her performative role and into authenticity. Still, the reality of her illness, and the power structures surrounding her, do not change.

Death as the Final Curtain

The film ends, as it begins, in grief. Satine dies in Christian’s arms just as they are about to escape, her final moments punctuated by blood and song. Her death fulfills the melodramatic trajectory of the tragic heroine—a woman punished for her desire to love and be free. The Duke loses. Christian loses. And most tragically, Satine never gets to fly away.

As Jones writes in her essay “Never Fall in Love with a Woman Who Sells Herself”, Satine “dies as she lived—a caged bird, unable to fly away, or alternatively, buy her way out.” Luhrmann, in his characteristic style, heightens this moment with theatrical grandeur, turning emotional devastation into visual poetry. The tragedy is not only Satine’s death, but the world that made her death inevitable.

Like the other films in the Red Curtain Trilogy, Moulin Rouge! is not interested in subtlety—it’s operatic, emotional, and theatrical to its core. It invites the viewer to feel everything, loudly and vividly. But underneath the sparkle, it tells a grim story about power, gender, and what happens when love is filtered through systems of ownership. Satine sings “Come What May,” hoping love can save her—but in the world of the Moulin Rouge, love alone is never enough.

Leave a Reply