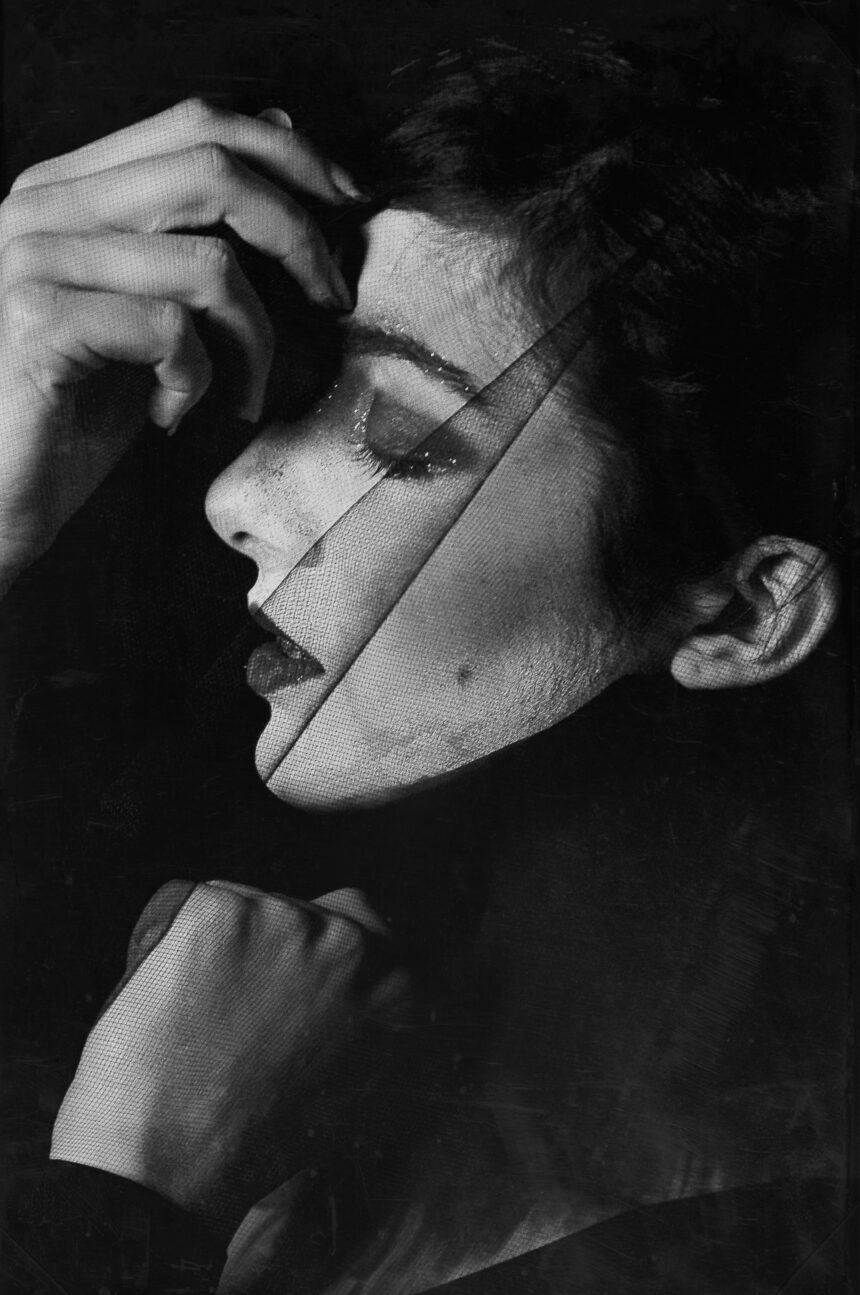

Photo by Emiliano Vittoriosi on Unsplash

What does it mean to “become” a woman?

Simone de Beauvoir’s famous line — “One is not born, but rather becomes, woman” — has never lost its relevance. But the more I sit with it, the more radical and heartbreaking it feels. In The Second Sex, Beauvoir doesn’t just question what it means to be a woman — she exposes how gender is used as a cage, a lifelong performance judged by men and enforced by society. And still, she dares to imagine a way out.

In revisiting her chapters on The Married Woman, Social Life, and The Independent Woman, I was struck by how painfully familiar her mid-century observations still feel. In Beauvoir’s time (and still, in so many ways, in ours), womanhood wasn’t something someone simply was — it was a role that had to be learned, earned, and constantly performed. And it’s not a performance that serves women. It serves men. It props up patriarchy.

Marriage as Transaction, Not Transformation

Beauvoir makes it clear that marriage, far from being a romantic fairytale, is a system of exchange — a man chooses a wife; a woman is chosen. Fathers hand off daughters; husbands gain caretakers. Women, in this setup, aren’t partners — they’re property. Even today, the echoes of this persist in how we talk about marriage as a “goal” for women, as if our value increases once we are chosen.

She writes that women are raised to perfect the art of “catching” a husband — comparing the process to flypaper. It’s not flirtation; it’s survival. A woman outside marriage is viewed with suspicion. Something must be wrong with her. She’s too ambitious. She’s queer. She’s difficult. She’s selfish. She’s not playing by the rules.

These judgments didn’t disappear with the 1950s. They’ve just morphed. Now we have “lean in” culture and pick-me girls and TikToks about being “wife material.” The language has changed. The logic hasn’t.

Dressing for the Gaze, Not the Self

In Social Life, Beauvoir digs into the everyday rituals that make women visible but not fully human: clothes, beauty routines, social codes. Men dress for utility. Women dress to entice — but never too much. It’s a tightrope walk: be sexy, but not vulgar; modest, but not frumpy; put-together, but not trying too hard. As Beauvoir notes, women are trained to view their bodies like their homes — things to decorate, maintain, and present for others.

This resonates with Laura Mulvey’s later concept of the “male gaze,” where women are framed as things to be looked at — eroticized, judged, consumed. The pressure to always appear attractive but not slutty, youthful but not immature, confident but not bossy — it’s exhausting. And it’s entirely gendered.

If a man wears sweatpants and skips shaving, it’s casual. If a woman skips makeup for a day, someone asks if she’s sick. That’s not vanity — that’s survival under a system that constantly surveils and disciplines women’s appearances.

Freedom ≠ “Easy”

Finally, Beauvoir’s reflections on The Independent Woman hit the hardest. Even in the 20th century, with women writing, working, and refusing to marry, society found new ways to shame and control them. An “independent” woman is still too often viewed as threatening or “easy” — as if sexual freedom and autonomy are the same thing.

Beauvoir explains that men struggle to see women as both subjects (with consciousness, agency, and purpose) and bodies (with desires and flaws). Instead, they reduce women to objects — beautiful, useful, discardable. Women who refuse this role are seen as unnatural. But maybe that’s the point: to disrupt what’s “natural” under patriarchy.

So What Now?

Beauvoir doesn’t offer easy answers, but she does leave us with a challenge. To transcend. To live outside the limits set for us. To recognize gender as constructed — and then to actively dismantle it. As she writes, “freedom is not given, it is taken.”

In today’s world, where gender is still policed (and weaponized), where bodily autonomy is under attack, and where women and queer folks are still fighting to simply be — Beauvoir’s work is both a warning and a call to action.

We are not born women. We become them.

And maybe we can unbecome them, too.

Leave a Reply