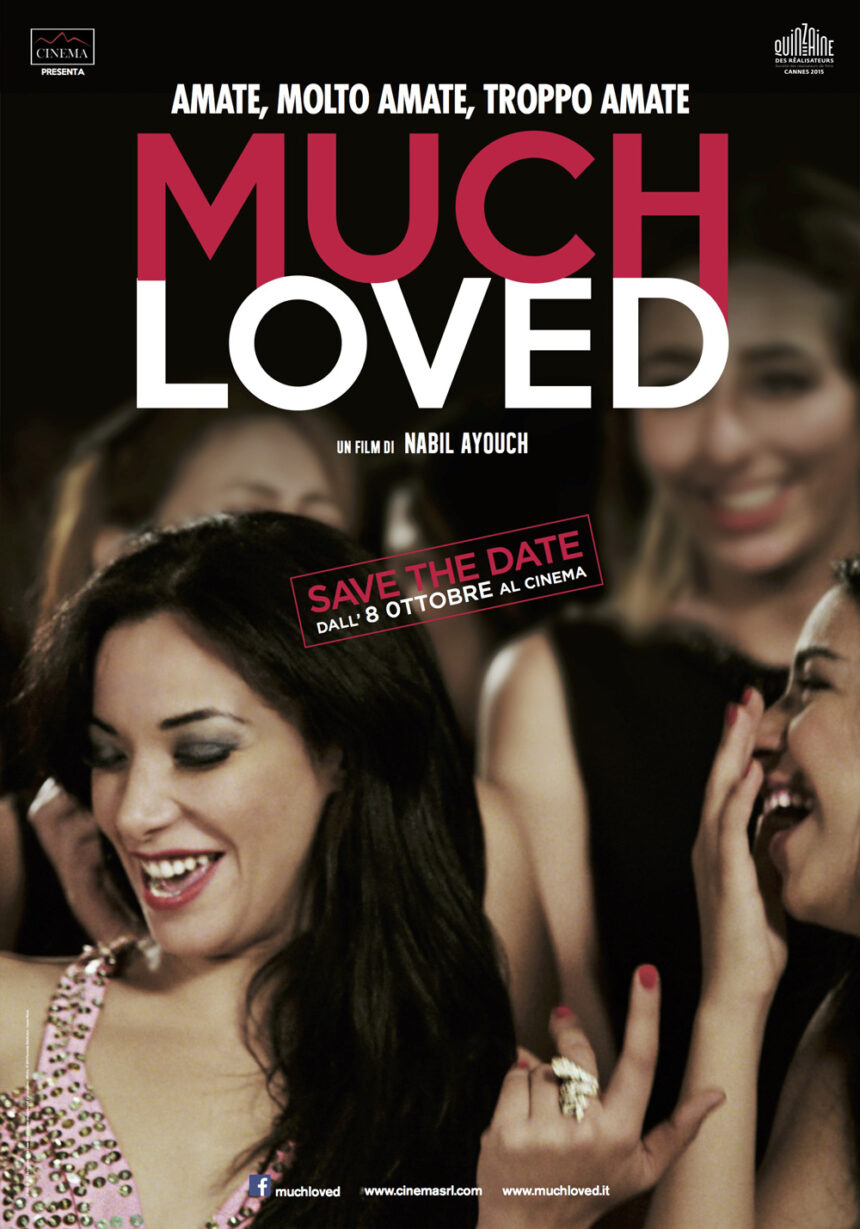

Sex workers all around the globe are judged and persecuted due to their career choice being different and controversial. In Morocco, things are not much different than in the U.S. (and many other countries) for prostitutes, as they face many battles through their way of making an income to support themselves and their families. Nabil Ayouch, director of Much Loved (2015), dives into the stories and experiences of prostitutes in Marrakesh, Morocco, where the four main protagonists live in this riveting film. Much Loved follows the experiences of four prostitutes in Marrakesh who face many obstacles and backlash due to their profession. Even with this backlash, Noha, Soukaina, Randa, and Hlima (the four main protagonists) are able to survive and show the audience that they are not much different than anyone else.

Nabil Ayouch is a French-Moroccan filmmaker who directed his most controversial film, Much Loved, in 2015. In “Much Loved Review – Tackles Sexual Hypocrisy in Morocco with a Battering Ram,” Phil Hoad writes that at the start of Ayouch’s research on this film, he began by interviewing around two-hundred sex workers over the course of eighteen months (Hoad). Ayouch learned about their backgrounds, why they became prostitutes, and stories of experiences being prostitutes in Morocco, according to “Nabil Ayouch on Much Loved (2015),” on YouTube (VPRO Cinema – YouTube). Within this same YouTube interview, Nabil Ayouch goes more in-depth on the toll it took on him, and the ways he was able to work with these stories. Ayouch explains that “he built stories based off of what the women had told him” about their lives and that “sometimes the stories were too much to bear” (VPRO Cinema – YouTube).

Much Loved premiered in Ayouch’s birthplace, France, but was banned in Morocco for its controversial portrayal of females in the country. The film is set in Marrakesh, Morocco which is “well known as a destination for sex tourists from Europe and the Middle East. Prostitution is a pillar of the city’s economy. More than 50 percent of the country’s prostitutes are supporting families, according to a Ministry of Health study conducted in 2012 but released last week,” according to Aida Alami of the New York Times in the article, “A Film on Prostitution Generates an Uproar” (Alami). This is evident in the film, as the four main women are prostitutes and there are many other sex workers shown throughout the film. For Marrakesh, Morocco being a “pillar of the city’s economy,” Much Loved still remains controversial due to the traditional views that leave these sex workers rejected from society and their families.

If being a sex worker in Morocco is so harshly rejected, why would Nabil Ayouch continue with creating this film, knowing that he might have received backlash? In the YouTube VPRO Cinema interview, Ayouch notes that he wanted to create a “portrait of four warriors who are fighting for their existence, their right to exist every day,” rather than a film of prostitutes being objectified, as what usually would happen (VPRO Cinema – YouTube). He wanted to let their stories be heard because they are also human beings who live very similar lives to us. According to Davies H. Kaya in the article, “Exoticism Or Empowerment? the Representation of Non-Normative Women and Prostitution in Nabil Ayouch’s Much Loved,” other than their work, “we are with them when they watch television, bicker, and sleep; we accompany them as they carry out mundane, quotidian tasks, such as going to the hairdressers and visiting family” (Kaya, 104). These people do the same everyday tasks that everyone else does, including having fun like watching television and having outings other than for work. When hiring actresses for this film, Ayouch made sure that the actresses knew what their roles were, in terms of not being a prostitute, but giving these women a voice through film (VPRO Cinema – YouTube). Hearing this shows how dedicated Nabil Ayouch really is about shedding light on sex workers and why they do what they do, and what they experience in their everyday lives.

Loubna Abidar is the actress who plays the role of Noha, the leader of the group. Noha keeps everyone focused and sets up most of their clients because she is the most experienced of the women. Loubna Abidar was originally hired as a consultant to Nabil Ayouch throughout the film to make sure that he accurately portrayed the prostitutes’ stories, as he is not a prostitute and not a woman, he did not want the film to be biased (VPRO Cinema – YouTube). When asked about her significance in playing the role of a prostitute in her first acting role, she says that “there are thousands of prostitutes in Morocco. You need to watch the movie to understand that there is much more to it” (Alami).

Abidar, along with Ayouch, points out the negative connotation behind the word ‘prostitute’ and they want to end the stigma behind it to show people the stories of sex workers in Marrakesh, Morocco. Due to her role in Much Loved, Abidar faced a large amount of hate, receiving death threats even (VPRO Cinema – YouTube). The people sending these threats are so wrapped up in their traditional views that they cannot fully understand the concept behind this film, making Ayouch’s goal (of telling the stories of these women) almost useless for this specific group, because they are too involved within their beliefs.

Along with these traditional views on prostitution, there are also very biased views on same-sex couples in Morocco. In one specific scene, Ahmed, one of Soukaina’s clients, is implied to be gay when he cannot perform in the bedroom and is exposed for having ‘gay porn’ on his laptop. He gets angered by Soukaina’s accusation and ends up beating her to the point where she has to go to the hospital (Ayouch, Much Loved). When hitting her, Ahmed says “You’re worth absolutely nothing, not even a cent! Not even half a cent,” which is something that he was taught growing up, showing that these ideas are drilled into his mind during youth, just as being gay is something that is drilled in as being forbidden (Ayouch, Much Love).

In the Morocco section of the website, OutRight Action International, there are many facts and details about LGBT views and rights in the country. The site states that same-sex relations are illegal and punishable with up to three years in jail, with a largely negative public opinion of LGBT people (OutRight Action International). This could be the reason why Ahmed lashed out at Soukaina over the accusation. His shame makes him violent, as that is how men are taught to cope, traditionally. Ahmed fears his being gay because he lives in an area that is not accepting of gay people, so he tries to blend in with the rest of Morocco by hiring a prostitute and doing as the other men around him are doing.

Prostitution alongside same-sex relationships is a threat to the “traditional values” of some Moroccans, due to the “hate speech from public officials and religious leaders” making it hard to change people’s views” (OutRight Action International). Back to Davies H. Kaya’s article on representation in the film, he writes that “the film thus shows that strict and inflexible rules regarding gender and sexuality constrain both women and men,” showing once again that prostitutes are stereotyped one way, but also that men are stereotyped as being super-strong, straight, and masculine (Kaya, 108). With these stereotypes created by traditional people, Ayouch tries to make an impact in reversing these views within Morocco.

Ayouch touches upon the subject of LGBT people, once again, in several scenes that include gay prostitutes. It is implied that the four main protagonists are friends with the gay prostitutes, almost removing all stigma behind LGBT people and prostitutes. They are all able to be friendly, including going out to dinner with them and hanging out together back at the apartment. These scenes humanize what Moroccans might call ‘society’s outcasts’ because these people that are criminalized are being shown doing tasks that normal people do, making them become one with the audience.

As mentioned earlier, Nabil Ayouch had the intention to humanize these contraversial character-types to allow the audience to be more open to not only prostitutes, but also LGBT people, like the person pictured above. These men dressed as women to get their clients because it would not look ‘right’ if two men were walking into a hotel together. Dressing feminine allowed for safer LGBT prostitution since LGBT relations are illegal in Morocco.

Another large issue within the traditional views behind prostitution is family honor versus shame. Kaya discusses how women rely on men for a steady income so when they become widowed or orphaned, women turn to prostitution to survive (Kaya). This is very similar to what Noha has done for her family. She makes money that she then gives to her mother, to help raise her siblings and children. Throughout the film, the audience can understand that Noha’s mother is not very happy with her choice of profession but mostly keeps her thoughts to herself. In one specific scene, her mother does not keep her opinions to herself, saying “Listen to me closely. Do not come to this house again. The neighbors talk about you and about what you do” (Ayouch, Much Loved). Noha’s mother isn’t just ashamed of her daughter, but she also has the burden of her neighbors knowing about her profession, making having her daughter over to her house really difficult. In response to her mother’s statement, Noha replies “Who’s your daughter, me or the neighbors? I need you. If I miss you, how will I see you?” (Ayouch, Much Loved). This reply shows that Noha is still human and she needs her mother. Noha is not held back by the stigma of prostitution, unlike the rest of her mother’s neighborhood.

This scene helps to make a connection between the stigmatizing and humanizing that is continually shown throughout this whole film. Along with the strong points made in Kaya’s article about family and shame, Bernhard Venema and Jogien Bakker make great points about shame that families feel when a member joins the profession of prostitution, in their article “A Permissive Zone for Prostitution in the Middle Atlas of Morocco.” They write that “virginity and chastity are central elements of this honor, so women’s behavior is strictly controlled by having them married off early, veiled, and prevented from playing a role in the public domain” (Venema and Bakker). As Noha (along with the other three protagonists) did not follow the traditional elements of family honor in Morocco, her mother has tried to put shame on her due to the stigma around prostitution.

In the end of the film, it is important to note what happens because it is not a very clear ending, to understand the women’s fates. The final scene includes all four main women sitting on the beach, relaxing with Said (their caretaker). In the article “Exoticism Or Empowerment? The Representation of Non-Normative Women and Prostitution in Nabil Ayouch’s Much Loved,” Kaya points out this last scence, writing that “given the frequent association of the shoreline with the trope of liminality, the setting of this final scene could be seen to emphasize the women’s marginalization in Morocco” (Kaya, 109). With this being said, the fates of each character is unknown but it is implied that these characters are stuck, as they know they will eventually have to go back home, but they do not know what their future holds. Looking off into the shoreline shows their contemplation for what is to come next, as they do not know and won’t know until they are back home and moving forward.

With Much Loved being such a contraversial film, discussing topics such as prostitution, women’s rights, and LGBT rights, there has been a large sum of backlash towards the film, director, and even some cast members. The film was banned in Morocco after a few clips had been released, before the actual film was released (Hoad). Many people who worked on the film received death threats and Loubna Abidar was even assaulted due to her role (VPRO Cinema – YouTube). Lastly, Nabil Ayouch was charged with making pornographic content (Kaya). This backlash goes to show the stigma that is behind prostitution. Ayouch created a film to humanize these women and the Moroccan government refused to even watch it before benning it. The banning of the film, threats to cast members, and even the assault, are examples that prove Ayouch’s points about the traditional views behind these topics.

In conclusion, Nabil Ayouch, director of Much Loved (2015), uses the stories of Moroccan sex workers to break the stigma behind prostitution and to humanize the women, as they are not much different than anyone else. Ayouch creates the plotline of Noha, Soukaina, Randa, and Hlima’s life to show the backlash they face from people including family, neighbors, and even their clients. Davies H. Kaya makes a brilliant point about the entirety of this film, writing that “Much Loved makes a brave, if contentious, intervention into highly topical current debates involving questions of gender, visibility, and freedom of expression in Morocco and the wider Arab world today” (Kaya, 99). This is a beautifully written way of wrapping up all the other points within this paper because Much Loved is not just a film about prostitution, but rather a story of power, shame, sexuality, abuse, gender roles, and the traditional views that interject throughout the entire film. Even with all the backlash that this film faces, Nabil Ayouch was able to make an impact through the making of Much Loved as he successfully humanized these women and demonstrated the backlash that they face due to their profession.

Leave a Reply