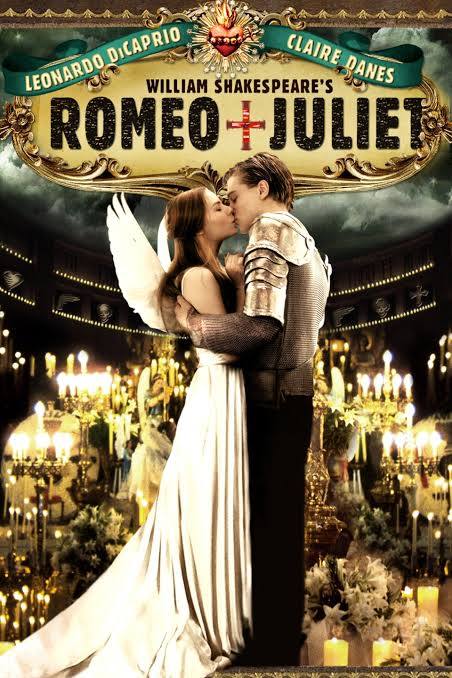

Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet (1996), the second film in his Red Curtain Trilogy, takes Shakespeare’s classic tragedy and throws it into the neon-lit chaos of modern-day Verona Beach. A dazzling blend of high drama, Catholic symbolism, Miami-inspired aesthetics, and MTV-era visuals, Luhrmann’s adaptation retains Shakespeare’s original language while reimagining the feud between the Capulets and the Montagues through guns, convertibles, and designer suits.

But beneath the visual excess lies a story deeply entrenched in societal expectations about gender. The performance of masculinity is front and center, literally exploding in the film’s opening gas station brawl. Meanwhile, women are pushed to the margins, expected to embody beauty and submission. By exploring the gender dynamics of this adaptation through theorists like Simone de Beauvoir and Judith Butler, we can better understand how Luhrmann critiques—and sometimes reinforces—the gendered expectations of both Shakespeare’s era and our own.

Masculinity Performed: Violence as a Social Norm

From the film’s very first scene, masculinity is tied to aggression. The Montague boys roll in blasting loud music, guns holstered, chewing cigars. Their loud bravado quickly erupts into a violent shootout with the Capulets. In this world, to be a man is to be armed, angry, and aggressive. Guns are omnipresent accessories, so common that people are expected to check them before entering public spaces—parties, pool halls, gas stations. It’s a ritualized performance of masculine dominance, and one that leaves little room for vulnerability or deviation.

Romeo, played by Leonardo DiCaprio, is an exception. When introduced, he’s removed from the chaos, scribbling poetry by the beach, mourning his love for Rosaline. His sensitivity and yearning for peace set him apart from his male peers. Yet Romeo’s deviation from traditional masculinity is mocked—his cousin Benvolio laughs off his heartbreak. Judith Butler, in Gender Trouble, reminds us that gender is performative: “If it is possible to speak of a ‘man’ with a feminine attribute… then it is also possible to speak of a ‘man’ with a feminine attribute… but still to maintain the integrity of the gender” (Butler, 2006, p. 33). Romeo’s peace-seeking nature does not make him less of a man—only less of a normative man in the violent world of Verona Beach.

Women as Objects of Exchange: Marriage and Social Capital

On the other end of the binary, women in Romeo + Juliet are mostly silent or sidelined, performing femininity through beauty and compliance. Juliet, played by Claire Danes, is introduced being primped and pampered before the Capulet party. Her mother and the nurse gossip about beauty and suitors, treating Juliet like a prized object to be presented, not a person with agency.

Juliet’s value is defined by marriage. Her parents want her to marry Paris, a wealthy and well-connected suitor whose face is literally on the cover of a magazine. The camera lingers on his image, commodifying him as a status symbol. This reinforces Simone de Beauvoir’s claim in The Second Sex: “She takes his name; she joins his religion, integrates into his class, his world… she becomes his other ‘half’” (Beauvoir, 1949/2010, p. 442). Juliet’s identity is not her own—it’s constructed around her relationship to a man.

When Juliet refuses to marry Paris, her father becomes violent, threatening to throw her into the street to starve or die. This chilling scene reveals the transactional nature of marriage. As Butler explains in her analysis of Lévi-Strauss in Gender Trouble, “The bride, the gift, the object of exchange constitutes ‘a sign and a value’… [which] consolidates the internal bonds… of each clan” (Butler, 2006, p. 52). Juliet is a bargaining chip, a means for her father to improve his social standing. Her refusal threatens that transaction, and thus threatens the family’s social order.

Even Juliet’s mother, who shows more compassion, ultimately begs her to comply—not out of cruelty, but fear. Beauvoir writes, “For young girls, marriage is the only way to be integrated into the group, and if they are ‘rejects,’ they are social waste” (Beauvoir, 2006, p. 441). Juliet’s mother fears her daughter’s rejection of the marriage plot will mark her as worthless in the eyes of society.

Non-Normative Characters: Resistance and Rejection

Romeo and Juliet may resist gendered expectations, but they’re not alone. Several other characters defy the norms in subtler ways, offering alternate paths within this rigid gendered world.

Friar Laurence, for instance, is agender and asexual. As a priest, he exists outside the system of marriage, romance, and reproduction. His commitment to peace makes him a quiet revolutionary within this hyper-masculine society. He is not violent, yet he’s the catalyst for the lovers’ rebellion, helping them marry in secret in hopes of ending the feud.

Mercutio, meanwhile, is flamboyant, theatrical, and gender-nonconforming. His Queen Mab speech is campy and chaotic, filled with innuendo and manic energy. Mercutio’s fluidity makes him difficult to categorize—he’s not interested in love or marriage, nor does he perform the stoic masculinity of his peers. He mocks Romeo’s sensitivity, yet defends his friend with ferocity. In this way, Mercutio exists on the margins, pushing back against binary expectations of gender.

Juliet’s nurse also operates outside normative gender roles. As an older, unmarried woman with deep affection for Juliet, she straddles the line between mother and servant. She participates in the secret marriage, defying Juliet’s parents, but ultimately urges Juliet to obey her father. Her shifting loyalties reflect the internalized norms older women have been forced to accept in order to survive.

Conclusion: Tragedy in the Face of Tradition

Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet is a glittering tragedy about love, fate, and family—but it’s also a story about the dangers of strict gender norms. Masculinity is tied to violence, and deviation from it leads to ridicule or death. Femininity is equated with beauty and obedience, and resisting it results in punishment or abandonment.

By weaving the philosophies of Beauvoir and Butler into the analysis, we see how gender functions not as a natural fact, but a social performance. Juliet’s rebellion is not just a romantic gesture—it’s a political one. Romeo’s peaceful heart is not weakness—it’s resistance. And in the end, their love collapses under the weight of a world that refuses to allow alternatives.

Luhrmann’s Verona Beach may be fictional, but the pressures its characters face are all too real. In their final act of defiance—dying for love on their own terms—Romeo and Juliet unmask the violent, performative systems that govern their world. In doing so, they leave us asking: what might gender look like, if we too dared to remove the mask?

Leave a Reply